Pushback fire up your browser

11 czerwca 2023Watching X-rays flung out into the universe by the supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy 800 million light-years away, Stanford University astrophysicist Dan Wilkins noticed an intriguing pattern. He observed a series of bright flares of X-rays – exciting, but not unprecedented – and then, the telescopes recorded something unexpected: additional flashes of X-rays that were smaller, later and of different “colors” than the bright flares.

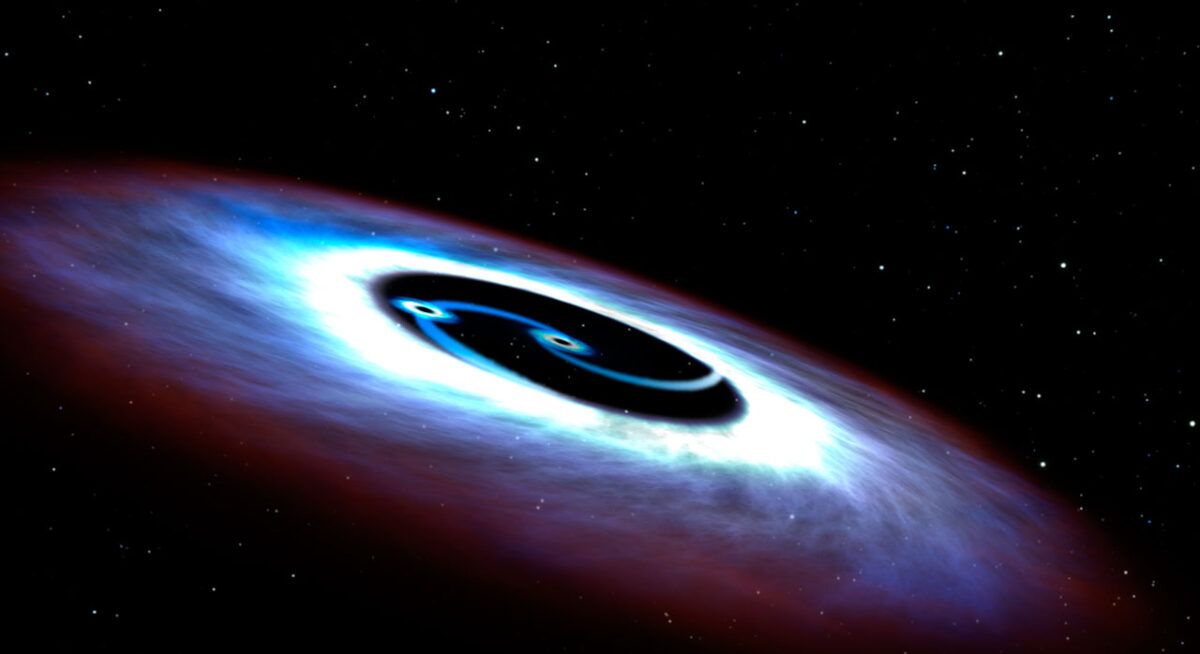

This artistic illustration is of a binary black hole found in the center of the nearest quasar to Earth, Markarian 231. Like a pair of whirling skaters, the black-hole duo generates tremendous amounts of energy that makes the core of the host galaxy outshine the glow of its population of billions of stars. Quasars have the most luminous cores of active galaxies and are often fueled by galaxy collisions. Hubble observations of the ultraviolet light emitted from the nucleus of the galaxy were used to deduce the geometry of the disk, and astronomers were surprised to see light diminishing close to the central black hole. They deduced that a smaller companion black hole has cleared out a donut hole in the accretion disk, and the smaller black hole has its own mini-disk with an ultraviolet glow. Links: NASA Press release Markarian 231, host galaxy of double black hole

Researchers observed bright flares of X-ray emissions, produced as gas falls into a supermassive black hole. The flares echoed off of the gas falling into the black hole, and as the flares were subsiding, short flashes of X-rays were seen – corresponding to the reflection of the flares from the far side of the disk, bent around the black hole by its strong gravitational field. (Image credit: Dan Wilkins)

According to theory, these luminous echoes were consistent with X-rays reflected from behind the black hole – but even a basic understanding of black holes tells us that is a strange place for light to come from.

“Any light that goes into that black hole doesn’t come out, so we shouldn’t be able to see anything that’s behind the black hole,” said Wilkins, who is a research scientist at the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at Stanford and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. It is another strange characteristic of the black hole, however, that makes this observation possible. “The reason we can see that is because that black hole is warping space, bending light and twisting magnetic fields around itself,” Wilkins explained.

The strange discovery, detailed in a paper published July 28 in Nature, is the first direct observation of light from behind a black hole – a scenario that was predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity but never confirmed, until now.

“Fifty years ago, when astrophysicists starting speculating about how the magnetic field might behave close to a black hole, they had no idea that one day we might have the techniques to observe this directly and see Einstein’s general theory of relativity in action,” said Roger Blandford, a co-author of the paper who is the Luke Blossom Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences, Stanford professor of physics and SLAC professor of particle physics and astrophysics.